I left the UW campus and walked out toward Highway 151 as I figured that someone could probably get me to De Forest from there. I spent some time looking at the lake--there's a big, beautiful lake right in Madison, and 151 goes along it. Then I decided to I'd better find a gas station if I was serious about hitchhiking to De Forest. It turns out I wasn't really. I waited for about an hour, then asked the man behind the counter how far De Forest was. He said it was less than half an hour by car, maybe 15 miles.

"What am I doing waiting here?" I said. "I could walk that in less than three hours."

"You have comfortable shoes?" he said.

"Yeah. I got them from a friend," I said, and I showed him my shoes.

"I've never heard of anyone walking to De Forest before," he said.

"Me neither," I said. Then I said bye and left.

It got dark about halfway through my walk. As I started being able to see what I assumed were the lights of De Forest, a police car pulled up behind me and turned on its mars lights. I turned around and tried to look past the headlights into the car. A policeman got out of the passenger side. He had a moustache, which no longer shocks me.

"Would you mind stepping over to the car?" he said.

"Sure, no problem," I said, and I went over to him.

"Drivers license," he said. Had I been speeding? I took out my wallet and gave him my license. "Your car break down somewhere around here?" he asked while giving my license to his partner in the car.

"I took a bus to Madison and started walking."

"Why not take a cab?" he said.

"I'm cheap," I said.

After a few more seconds his partner nodded to him and the policeman who had called me over, the one standing next to me, said, "I'm going to have to ask you get in the car."

"Am I under arrest?" I said.

"No," he said. "We're just going to take you to the station and ask you some questions."

I said OK and got in the car, and we drove into town. It turns out I was only about two miles away when they picked me up. The one policeman I had talked to led me up the handicapped-accessible ramp into the station, and then he brought me into a small room with walls made of bricks, a mirror, a table with two chairs, and a bare lightbulb in the ceiling. I looked at the mirror.

"People on the outside can see through that, can't they?" I asked.

"I'll ask the questions, OK?" he said.

"You bet," I said.

"Where were you this morning?" he said.

"Madison," I said.

"You weren't at the Holiday Inn Express?"

"No. But I bet my brother Horace was."

"Your brother Horace?"

"Yeah, he's one of two identical triplet brothers I have. The other one's name is Sebastian," I said.

"Identical triplets."

"That's right."

"I don't think those exist."

"Well, maybe I don't exist," I said.

"Don't get smart," he said. "So, you and your 'brother,' you, uh, what do you do?"

"Like with our lives?"

"Like for money. Yes."

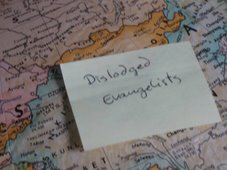

"We're dislodged evangelists," I said.

He looked doubtfully at me.

"Let me ask you something," I said.

"I said, I'll do the--" but I interrupted him.

"Have you ever become disembedded from your sensual experience?"

"That sounds like a personal question," he said.

"It is. Has, in your view, sense-based reality ever stopped cohering suddenly?" I started feeling very thirsty, and started wondering what in the world Horace had done at the Holiday Inn Express.

"So you're telling me you're some kinda guru," he said.

"What I'm telling you," I told him, "Is that I'm trying to tell people the good news, but because reality is no longer intelligible to anyone, and as our modes of communication have helped the unintelligibility, the only way to speak is with symbols, metaphors, and heightened academic-sounding nonsense speech. None of which anyone understands. So telling people the good news becomes exceptionally confusing for everyone involved."

"I don't understand," he said.

"Exactly," I said.

He looked at the ground thoughtfully for a minute.

"You're not a bad guy," he said. Then he raised his eyes to me, big, soft, brown eyes. "But I think you're crazy. What do you think about that?"

I thought for a moment. "Don't they tell you in interrogation school that crazy people don't think they're crazy?" I asked him.

"I didn't go to interrogation school," he said, and took a breath while looking at his watch. "How do I know you actually have an identical brother?"

"I can tell you what he looks like," I said.

"Let me guess: exactly like you."

"Well, there are subtle differences."

"Such as?"

"He has a beard and a hat and sunglasses."

"So you're telling me he looks like one of those Santa Claus commercials," he said.

"That was good," I said. Maybe this guy actually did go to interrogation school. "He also wears a blue jumpsuit," I said.

"OK," he said. "Accurate description. How do I know you didn't just change your clothes and shave after this morning's events?" he said.

"And then what?" I said. "Did I flee De Forest only to decide to come back? On foot? At night?"

"The criminal always returns to the scene of the crime," he said lamely. I noticed that he looked exceptionally bored.

"Look," I said. "What did Horace do this morning that was so bad?"

"He stood on a table and talked crazy and dumped a bunch of Honey Nut Cheerios in a sink," he said.

"And you can arrest him--me--for that?" I said.

"Well..."

"Is that a crime in Wisconsin?" I said. "No, it's not a crime. What, did he scare some people?"

"Yeah," said the policeman. "He scared some people pretty bad."

"He was probably trying to evangelize them," I said. "That's what we do."

"Do you."

"Yes."

"I don't believe it."

"At this point, my brother Sebastian would probably say, 'Deep in your organs you know that the air you think you breathe is not really the air as it is. Thought. Mind. Eyeballs! What matches up? Real air. Real air is from the starboard bow, it sprays, it dazzles! It is cold.' That's from a poem he wrote."

"You my friend," he said, "Are going to jail."

Which is where I am now. Strangely, we get to use the internet sometimes. Horace, if you read this, could you please come bail me out of the jail here? Sebastian, perhaps you could wire some bail money.

The guard is yelling.